Identify a key political or social movement in modern history and assess its impact

Introduction

“Garibaldi met with such a reception as no one ever had before”, Lord Palmerston.[1]

On Monday 11 April 1864, half a million people crammed into the streets of London, anxiously awaiting the arrival of Italy’s revolutionary hero Giuseppe Garibaldi. At two-thirty in the afternoon, London witnessed a moment unique in history, as hundreds of thousands of people were brought together with impeccable unity to celebrate the arrival of one man, famously described by A. J. P. Taylor as “the only wholly admirable figure in modern history.”[2] Yet this immense moment has largely dissipated into historical obscurity, remembered only in the name of a few pubs and two streets in all of London.

Indeed, Garibaldi’s visit receives remarkably little attention even by historians of nineteenth century London. When studied, it is almost always treated as an isolated historical event, unconnected to broader domestic British political events and issues. The idea that British politics and society could have been greatly shaped simply by the single visit of one man, who spoke little English and did not represent any state government, was difficult for traditional nineteenth century high-political historians to countenance.

This paper contends, however, that in reality this “Garibaldi moment” had a profound impact on the British political landscape. Most significantly, its legacy can be found in the British suffrage movement and the Great Reform Act of 1867. To evidence this, I will be exploring the diaries, speeches, recollections and letters of the key individuals within this suffrage movement. Alongside this, I will be examining the records of the Reform League, which played an influential role in the legislative outcome. Before continuing, however, it is first necessary to briefly explore Garibaldi’s visit to London.

The Garibaldi Moment

As Garibaldi disembarked the train in London, he was immediately greeted by representatives of the London Working Men’s Committee, whom he agreed to meet with the following week at the Crystal Palace.[3] Upon leaving the station, the General met with a flood of cheering people before being escorted to a carriage where he travelled through the crowds, standing and waving his appreciation as best he could. This journey is best captured in the diary of the civil servant, Arthur Munby:

The excitement had been rapidly rising, and now, when this supreme moment came, it resulted in such a scene as can hardly be witnessed twice in a lifetime. That vast multitude rose as one man… they leapt into the air, they waved their arms and hats aloft, they surged and struggled round the carriage, they shouted with a mighty shout of enthusiasm that took one's breath away to hear it: and above them on both sides thousands of white kerchiefs were waving from every window and housetop... This today has been the greatest demonstration by far that I have beheld or, probably, shall behold.[4]

In this account, Arthur Munby expresses greater amazement towards the spectacle of the immense crowd than he does to the actual sight of Garibaldi. Through reading Munby’s full entry, a Burkean sense of the ‘sublime’ emerges, where the mass of the crowd creates an image of a beautiful yet terrifying power, softened only by the distance Munby gains from his step into the tobacco shop.[5]

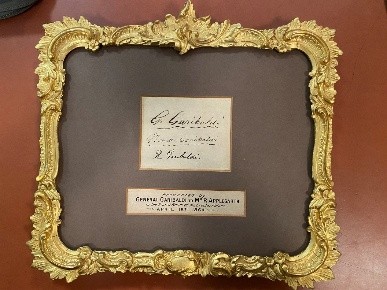

The shock of the enormity of Garibaldi’s reception forced Palmerston’s government into officially recognising Garibaldi’s presence, where Palmerston himself even dined with Garibaldi two days later to gain some control over the general’s plans.[6] Garibaldi, resultingly, limited his public engagements, holding only two major receptions, both at the Crystal Palace on 16 and 18 April. Tickets for these events rapidly sold out, leaving thousands of onlookers forced to watch from outside the grounds as the General gave his addresses.[7] As earlier agreed, Garibaldi met a deputation of the London Working Men’s Committee, where he gifted them his autograph. Framed Garibaldi Signature (1864)[8]This act affirmed in the minds of the working people of London that Garibaldi’s visit was for their pleasure and not for the establishment elites. However, this popularity among the working classes alarmed both Queen Victoria and the Government, which is why, two days later, it was suddenly announced that Garibaldi would be returning to Italy, ostensibly for “health reasons”.[9] In reality, Garibaldi’s early departure came at the request of the Government, a fact that became clear when it emerged in the papers that William Gladstone had met in private with Garibaldi a day before the announcement. [10]

Framed Garibaldi Signature (1864)[8]This act affirmed in the minds of the working people of London that Garibaldi’s visit was for their pleasure and not for the establishment elites. However, this popularity among the working classes alarmed both Queen Victoria and the Government, which is why, two days later, it was suddenly announced that Garibaldi would be returning to Italy, ostensibly for “health reasons”.[9] In reality, Garibaldi’s early departure came at the request of the Government, a fact that became clear when it emerged in the papers that William Gladstone had met in private with Garibaldi a day before the announcement. [10]

This immediately led to the London Working Men’s Association and the Garibaldi Committee to host emergency “indignation” meetings in protest against the government’s decision. One such meeting, held on Primrose Hill and chaired by Edmund Beales, resulted in the police dispersing those gathered, which elicited yet further condemnation of the government's actions. Indeed, the Home Secretary, George Grey, faced questions in parliament over the incident, where he denied giving “any special instruction to the police,” yet admitted, “it might have been as well to have allowed the meeting to have continued”.[11] Nevertheless, those present at the failed meeting are said by Frances Gillespie to have readjourned at a local tavern and “determined then to start a Reform League”.[12]

The Reform League

On March 23rd 1865, the Reform League was formally established, with Edmund Beales being elected president.[13] Similarly to Beales, E. D. Rogers, who had been active during the Garibaldi visit, was elected chairman of the League's finance committee.[14] The Reform League advocated for manhood, the extension of suffrage to working males, and for the secrecy of the ballot.[15]

Initially, in early 1865, the Reform League struggled to grow its membership, for Palmerston’s liberal government carefully offered enough reforms to keep revolutionary sentiments low. As Hollyoake rightly wrote, it appeared that reform could “be refused with more safety now than at any time since 1832.”[16] However, Palmerston’s death in October 1865 completely changed this political atmosphere. John Russell initially took over as prime minister and, in a bid to gain parliamentary support, drafted the 1866 Reform Bill. The Reform League was not consulted and criticised it as fundamentally “oppressive” and “unsound”.[17] Russell’s government soon fell apart, and the bill was never passed, leading to the succession of the minority Conservative government led by Lord Derby.

Representative of the Reform League, John Bright, argued that the ascension of the Conservative government represented “a declaration of war against the working classes”, which immediately afforded the league greater manoeuvrability of political action.[18] The League, influenced by the Garibaldi moment two years earlier, decided to stage mass protests in favour of reform. Bright himself had remarked after the Garibaldi visit, “If the people would only make a few such demonstrations for themselves, we could do something for them.”[19] After a few minor demonstrations in June 1866, the League attempted to organise its largest rally yet at Hyde Park. It is estimated that around 200,000 workers participated in this demonstration, a number around eight times that of the infamous Chartist march at Kennington Common, though still not quite half that of what Garibaldi received.[20] Initially, police barred the gates to the park, yet under the pressure of the crowd, some railings gave way, and thousands poured in, trampling on the Queen’s flowers as they did so.[21]

This marked a significant embarrassment to the new Derby-Disraeli government and ensured that the call for reform could not be ignored. Yet equally, the violence and vandalism displayed during the protest isolated many moderates and caused the League to suspend all further marches.[22] In the following months, the League entered slow negotiations with the government. In May, taking the initiative to regain popular support, the League appointed Garibaldi as its honorary president. Garibaldi replied with typical humbleness in a letter that was later widely publicised:

Honorary President of the Great League of the English working men! This is indeed the most precious title that you could offer to me, your countryman, myself truly a son of the people, and a working man in heart and arm. In the immense laboratory of the human family, England is justly the captain of the great movement for our rights and our emancipation, and our unhappy but good population here will be proud to follow your example in the glorious path which you have traversed.[23]

Garibaldi’s support for the League amplified pressure on the Government to enact reform legislation, and after protracted discussions, finally, on the 15 August 1867, the Reform Act was signed into law. This Act was far more revolutionary than the proposed bill of Russell in 1866 and expanded the vote to over 1,500,000 men.[24] The Reform League, having largely fulfilled its goals, eventually dissolved in 1869.

Conclusion

This paper, although brief, has sought to show that the “Garibaldi moment” had a greater impact on nineteenth century Britain than is traditionally understood by historians. This becomes clear when a closer examination of the inner machinations and papers of the Reform League is conducted. The leading figures of the League, Beales, Bright, Cowen and Taylor, were all active during the Garibaldi visit and were profoundly influenced by the unity shown by the London Workers during the General’s stay. They sought to recreate this, and favoured mass demonstrations over all other forms of protest. Indeed, after the successful, yet politically controversial march in Hyde Park, the League sought to regain the support it lost from the moderates by appointing Garibaldi as honorary president. It is undeniable that the visage of Garibaldi loomed over London long after his yacht departed for Italy, rearing itself again in the ideas and tactics that pervaded the suffrage movement of 1866–67.

For more sources related to those discussed in this essay, please see our collection, Trade Unionism and the Chartist Movement, 1833–1910.

[1] The National Register of Archives, Broadlands papers, Palmerston's diary, 11 April.

[2] A. J. P. Taylor, The Italian Problem in European Diplomacy, 1847–1849 (Manchester, 1934), 7.

[3] Liverpool Mercury, 11 April, 1864, available at https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/, accessed 19 May, 2025.

[4] Cambridge, Trinity College Library, MSS, Munby's diary for 11 April, 1864.

[5] See: Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (New York, 1958; 1st edn. 1757).

[6] Western Daily Press, 11 April, 1864, available at https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/, accessed 19 May, 2025.

[7] Cornish Echo and Falmouth & Penryn Times, 16 April, 1864, available at https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/, accessed 19 May 2025.

[8] Bishopsgate Institute London, 372, Holyoake/11.

[9] The Times, 20 April, 1864, cited in Marcella Sutcliffe, “Garibaldi’s visit to London”, History Today (2014), 52.

[10] L. Hunt, “The Anti-Garibaldi Plot Revealed”, The Examiner, no. 2934, 23 April, 1864, available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/8672899.

[11] General Garibaldi, "Meeting on Primrose Hill", 25 April, 1864, Hansard, vol. 174. cc.1549–50, available at https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1864-04-25/debates.

[12] Frances E. Gillespie, Labor and Politics in England, 1850–1867 (London, 1966), 219 and 250–51.

[13] Aldon D. Bell, “Administration and Finance of the Reform League, 1865–1867”, International Review of Social History 10, no. 3 (1965).

[14] Ibid., 396.

[15] Ibid.

[16] G. J. Holyoake, The Liberal Situation: Necessity for a Qualified Franchise (London, 1865 ), 34; TSSA. 1865, pp. 3–4.

[17] Robert Saunders, Democracy and the Vote in British Politics, 1848–1867: the Making of the Second Reform Act (Farnham, 2011), 227.

[18] Maurice Cowling, Disraeli, Gladstone and Revolution: the Passing of the Second Reform Bill (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), 249.

[19] R. A. J Walling, ed., The Diaries of John Bright (London. 1930), entry for 11 April.

[20] See John Cannon, “Hyde Park Riots (1866)”, The Oxford Companion to British History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[21] Ibid.

[22] Saunders, Democracy and the Vote in British Politics.

[23] British Online Archives, Trade Unionism and the Chartist Movement, 1833–1910, “Reform League Papers and Press Cuttings, June 1865–Jan 1869”, 29 May 1867 available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/3350/reform-league-papers-and-press-cuttings-june-1865-jan-1869#?xywh=0%2C-1279%2C2837%2C5031&cv=73, image 74.

[24] Cowling, Disraeli, Gladstone and Revolution.