"The Legacies of Britain’s Involvement in Transatlantic Slavery can Still be Felt Today." Discuss.

Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade was not merely a historical episode of moral failure, it was a defining force that shaped the nation's economic, political, and social foundations. Between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, Britain became one of the largest and most influential players in the trafficking of enslaved Africans, embedding racialised exploitation into the structures of empire, finance, and governance. While the abolition of slavery is often framed as a moment of national redemption, this narrative overlooks the deep and enduring legacies that slavery left behind. These legacies are not confined to history books—they are etched into contemporary inequalities, institutions, and public memory.

This essay argues that the legacies of Britain’s involvement in transatlantic slavery can still be felt today. Drawing on primary sources ranging from legislative records and economic documents to cultural artefacts and personal testimonies, it contends that slavery’s consequences are not relics of the past—they are realities of the present. Through an examination of the economic systems built on slavery, the selective ways it is remembered or erased, and the persistence of racial injustice in modern Britain, this essay makes the case that Britain’s involvement in slavery is not a closed chapter in history, but an ongoing influence on the country’s structural landscape.

Slavery as Foundation, Not Footnote

To understand how the legacies of slavery persist, we must first examine how deeply embedded it was in Britain’s institutional and economic foundations. Far from being a marginal chapter in history, slavery was a central engine of British imperial power.

A close analysis of primary documents reveals the scale and brutality of Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Between 1640 and 1807, British ships transported over three million Africans across the Atlantic.[1] These statistics—preserved in port records and customs archives—reflect more than just numbers; they expose the industrial scale of racialised violence and the economic infrastructure built upon it. Parliamentary sources such as the 1789 testimony of abolitionist William Dolben describe “130 slaves stowed in a space no more than 16 feet square”, offering a stark window into the horrors of the Middle Passage.[2] Such testimonies are vital not only for their vivid depictions of inhumanity but also for what they reveal about Britain’s legal and political complicity in sustaining this system.

Corporate records further underline the structural entrenchment of slavery. The Royal African Company, granted a royal charter to monopolise trade with West Africa, was responsible for transporting over 100,000 enslaved people in the late 17th century.[3] These were not rogue acts of cruelty but organised, state-backed commerce. This foundational role of slavery in Britain’s rise to global dominance continues to shape today’s economic disparities and the global imbalance between colonisers and formerly colonised nations.

Economic Legacies: Capitalism Built on Enslavement

The wealth that underpinned Britain’s rise as a global economic power was inseparably linked to slavery—a system that embedded racialised exploitation into the structures of finance, industry, and trade. Slavery was not simply a moral catastrophe; it was foundational to the development of British capitalism. As the historian Eric Williams argued in Capitalism and Slavery, British industrialisation was partly financed by profits from slave labour[4]. The wealth amassed from slave-produced goods—sugar, cotton, tobacco—was channelled into emerging industries, fostering the growth of manufacturing, finance, and trade networks. These economic transformations were not incidental; they were shaped by capital derived from slavery. This connection underscores how British capitalism was built upon the exploitation and commodification of human lives. Far from being a secondary element, slavery was woven into the fabric of Britain’s economic ascent.

Moreover, physical sites provide further evidence of slavery’s enduring economic legacies. In Bristol, for instance, the Exchange building, constructed in the 1740s, became a bustling centre for merchants involved in the slave economy.[5] The building’s architectural details—such as carvings of exotic animals and the heads of an African woman and an Indian man—are not mere decorative features; they are stark reminders of the city's direct connections to the slave trade (Figure 1).[6] These structures were more than commercial hubs—they embodied the wealth that slavery generated and the racial hierarchies it upheld. Indeed, many of Britain’s cities are physically intertwined with the profits of the transatlantic slave trade, and these architectural reminders continue to reflect the persistent economic inequalities tied to that history. Figure 1Even after the formal abolition of slavery in 1833, the economic benefits of the slave trade remained entrenched within British financial structures. The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act allocated £20 million in compensation to slave owners, a staggering sum at the time, but no restitution was offered to the formerly enslaved.[7] The compensation records, now digitised by UCL’s Legacies of British Slave-ownership project, demonstrate how the British government prioritized the interests of slave owners while completely disregarding the rights of those who had endured enslavement.[8] This prioritisation of capital over justice highlights how Britain’s racialised economic system was not dismantled but rather repackaged, perpetuating racial inequalities under the guise of a post-slavery society.

Figure 1Even after the formal abolition of slavery in 1833, the economic benefits of the slave trade remained entrenched within British financial structures. The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act allocated £20 million in compensation to slave owners, a staggering sum at the time, but no restitution was offered to the formerly enslaved.[7] The compensation records, now digitised by UCL’s Legacies of British Slave-ownership project, demonstrate how the British government prioritized the interests of slave owners while completely disregarding the rights of those who had endured enslavement.[8] This prioritisation of capital over justice highlights how Britain’s racialised economic system was not dismantled but rather repackaged, perpetuating racial inequalities under the guise of a post-slavery society.

Cultural Legacies: Education, National Memory, and Selective History

Beyond the economy, Britain’s cultural institutions have long perpetuated selective memory. The glorification of abolitionist figures—most notably William Wilberforce—has often overshadowed the extent of Britain’s involvement in slavery. [9] This distortion is especially visible in schools. A 2007 review of Key Stage 3 history syllabi by the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) found that most textbooks emphasised Wilberforce’s moral campaign while downplaying the brutality of slavery and Britain’s deep complicity.[10] This curated narrative of moral superiority—Britain as the nation that ended slavery—eclipses a longer, more violent reality: that Britain built its wealth on slavery and embedded racial hierarchies into the national fabric.

This historical sanitisation has consequences. A 2015 House of Commons debate on Black History Month (transcribed in Hansard) features MPs highlighting the “serious lack of understanding among young people about Britain’s role in slavery.”[11] That such observations remain necessary in Parliament underscores how deeply embedded historical erasure has become in national consciousness. When the public is unaware of or misinformed about their country’s past, it becomes harder to understand the structural nature of racial inequalities today, or to support meaningful reparative justice.

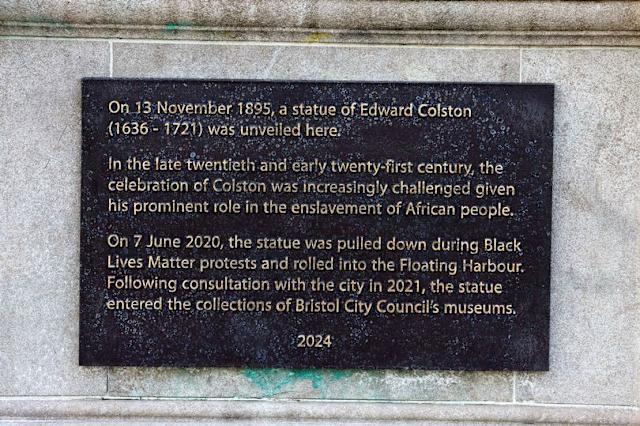

Monuments and statues are also powerful tools of public memory, often reinforcing selective versions of Britain’s colonial past. Edward Colston—a senior figure in the Royal African Company, which trafficked tens of thousands of enslaved Africans—is a striking example. His statue in Bristol stood for over 125 years until protestors pulled it down during the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement. Figure 2 shows the new plaque now installed on the plinth in 2024, which explicitly names Colston’s role in the slave trade and omits the earlier inscription praising him as a “city benefactor.”[12] The original 1895 dedication speech made no mention of slavery, revealing how public monuments once whitewashed histories of violence. Today, the statue’s removal and reinterpretation signal not an erasure of history but a demand to confront it honestly, challenging Britain’s sanitised narrative and forcing a reckoning with the ongoing realities of racial injustice. Figure 2

Figure 2

Institutional Injustice and the Ongoing Struggle for Reparations

The institutional legacy of slavery remains deeply embedded in contemporary British society, with racial disparities persisting across policing, housing, employment, and healthcare. The Windrush scandal, in which British citizens of Caribbean descent were wrongfully detained, denied healthcare, or deported, exemplifies how state policies continue to harm Black communities.[13] The testimony of Paulette Wilson, detained after over fifty years in the UK, illustrates this dehumanisation: it is not only bureaucratic failure, but a legacy of colonial logics that question Black belonging in Britain.[14]

Such structural injustices have fuelled renewed calls for reparations not as charity, but as a long-overdue reckoning. Though the demand for reparative justice is often framed as a modern issue, it has deep historical roots. As early as 1835, Jamaican campaigners petitioned the British Parliament, demanding that “those who have profited from our labour repair the injuries done to us.”[15] This early call highlights how formerly enslaved people were among the first to articulate the need for reparations. More recently, the issue has gained some traction through CARICOM’s Ten-Point Plan (2014), which formalised demands for historical accountability.[16] However, while this has sparked discussion, responses from British institutions remain limited. A notable example is the University of Glasgow, which in 2019 committed £20 million to reparative initiatives after uncovering financial links to slavery.[17] This rare instance of institutional reckoning demonstrates how British institutions are slowly confronting their complicity in the legacy of slavery. Yet, broader resistance remains strong. As Darrick Hamilton argued in his 2024 Henry Cohen Lecture, “reparations start with truth [. . .] but Britain has not yet had its truth-telling moment.”[18] Until that reckoning takes place, the economic, institutional, and psychological legacies of slavery will remain unresolved.

Conclusion: Legacies Lived, Not Left Behind

Primary sources—from parliamentary debates and compensation ledgers to curriculum reviews and personal testimonies—offer undeniable evidence of the enduring legacies of Britain’s involvement in transatlantic slavery. These are not mere historical facts; they are living structures that continue to shape contemporary Britain. From the wealth embedded in its institutions, to the racial inequities that persist, to the cultural erasures in education and public memory, the past is not past. It is present.

To say that the legacies of slavery can still be felt today is not an abstract claim. It is an observable reality, supported by documentation, architecture, personal experience, and institutional history. The question, then, is not whether these legacies exist but what Britain is willing to do about them. Without a national commitment to truth-telling, reparative justice, and structural reform, these legacies will not just linger, they will deepen. Britain’s future depends on its willingness to confront its past, not as a distant moral failing, but as an unfinished and ongoing story.

For more sources related to those discussed in this essay, please explore the extensive range of primary source collections that we have grouped under the themes of “Colonialism and Empire” and “Slavery and Abolition”.

[1] Kew, The National Archives, “British Transatlantic Slave Trade Records,” last modified September 12, 2023, available at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/british-transatlantic-slave-trade-records/.

[2] W. O. Blake, The History of Slavery and the Slave Trade, Ancient and Modern (Columbus, OH: H. Miller, 1860), 260, available at https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.historyofslavery00blak/?sp=260&st=text.

[3] Robin Law, “The Royal African Company of England in West Africa 1681–1699,” British Academy Review, no. 11 (2008): 31–34, available at https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/577/11-law.pdf.

[4] Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1944), available at https://glc.yale.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/capatlism_and_slavery.pdf.

[5] Google Arts & Culture, "The Legacy of British Slavery," available at https://artsandculture.google.com/story/oQURYPOdDSt8KA.

[6] Historic England, "The Exchange, Bristol," The National Heritage List for England, entry number 1298770, available at https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1298770.

[7] H.M. Government, The Compensation (England and Wales) Act 1991, available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Will4/3-4/73/1991-02-01/data.pdf.

[8] "Legacies of British Slavery," University College London, available at https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/.

[9] Annick Cossic, "William Wilberforce (the sociable voice of abolition)," Digitens: The Digital Encyclopedia of British Sociability in the Long Eighteenth Century, available at https://www.digitens.org/en/notices/william-wilberforce-sociable-voice-abolition.html.

[10] Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, Annual Report and Accounts 2007–08, HC 760, presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, July 2008.

[11] "Black History Month," Hansard, House of Commons, Westminster Hall, 21 October 2015, vol. 600, available at https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2015-10-21/debates/15102161000003/BlackHistoryMon.

[12] BBC News, “Edward Colston: New Plaque on Slave Trader’s Statue Plinth Unveiled,” BBC News, 17 April, 2025, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c3v9zglgz16o.

[13] BBC News, “Windrush Generation: Who Are They and Why Are They Facing Problems?”, BBC News, 18 April, 2018, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43782241.

[14] Diane Taylor, “‘I Can’t Eat or Sleep’: The Grandmother Threatened with Deportation after 50 Years in Britain,” The Guardian, 28 November, 2017, available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/nov/28/i-cant-eat-or-sleep-the-grandmother-threatened-with-deportation-after-50-years-in-britain.

[15] "Jamaica, Slavery—Petition of 1835," Hansard: House of Lords Debates, 27 February, 1835, available at https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1835/feb/27/jamaica-slavery.

[16] Caribbean Community (CARICOM), "CARICOM Ten Point Plan for Reparatory Justice", 2014, available at https://caricom.org/caricom-ten-point-plan-for-reparatory-justice/.

[17] University of Glasgow, "Historic Agreement Sealed Between Glasgow and West Indies Universities," 23 August, 2019, available at https://www.gla.ac.uk/news/archiveofnews/2019/august/headline_667960_en.html.

[18] Dennis Francis, "PGA Remarks at the New School on the Transatlantic Slave Trade, Its Legacies, and the Pursuit of Reparatory Justice," United Nations, 23 April, 2024, available at https://www.un.org/pga/78/2024/04/23/pga-remarksat-the-new-school-on-the-transatlantic-slave-trade-its-legacies-and-the-pursuit-of-reparatory-justice-as-part-of-the-2024-henry-cohen-lecture-series/.